Five Years After Awaab’s Death, Families Still Live in Danger

Kyle (a pseudonym), his pregnant wife and their two children had only been in their three-bedroom Greater Manchester rental a matter of weeks when he first spotted patches of mould creeping across the bedroom wall.

He tried wiping it off, but the dark stains quickly returned. That was when he realised the house had a serious moisture problem.

“It spread across the walls and even into the sockets,” he remembers. “The plugs would blow because water had seeped inside them.”

The family ended up throwing out clothes, children’s toys, beds and even TVs ruined by damp.

Kyle says there came a point when all four of them were forced to sleep on the living-room floor. Even after his wife came home from hospital with their newborn, they could not use the bedrooms. The landlord simply painted over the mould, he claims, instead of dealing with the cause.

Seven miserable months later, they left the privately rented home. Kyle, who works in admin, says the experience was emotionally draining. “It was horrendous. I felt completely lost and on the verge of tears most days.”

The problem Kyle faced is far from unique. Official statistics show that in 2023-24, around 1.3 million homes in England had damp in at least one room. That is roughly 5 percent of all housing. Worryingly, more than a million children are living in such conditions.

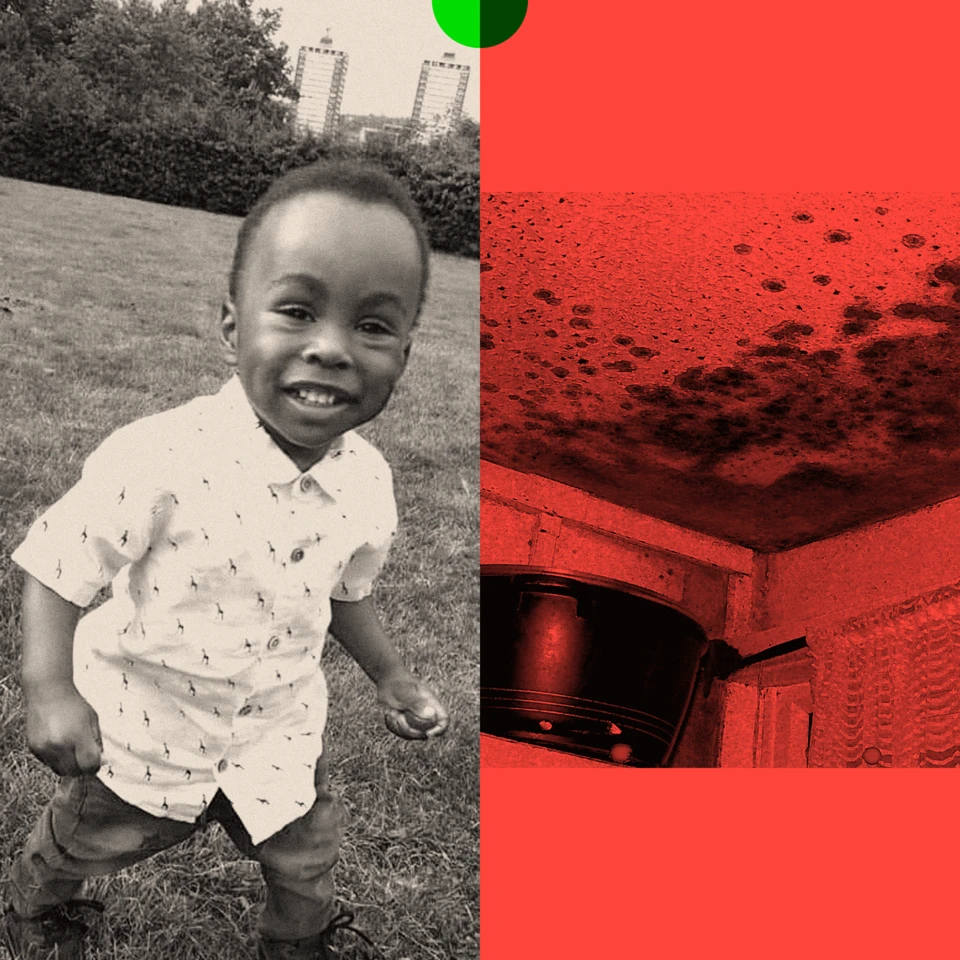

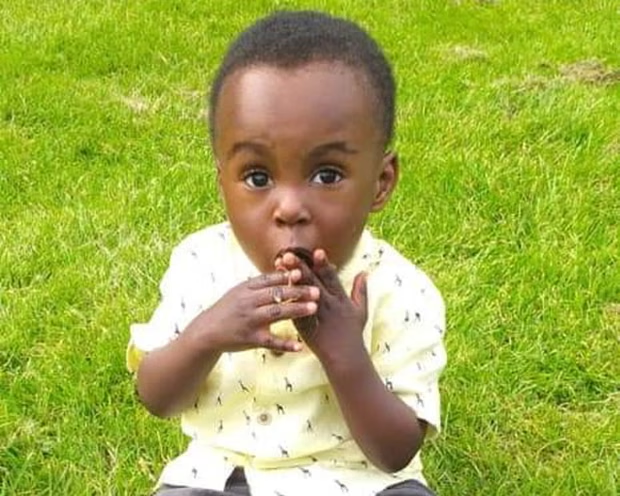

This situation persists despite nationwide shock over the death of two-year-old Awaab Ishak in 2020. He died after prolonged exposure to mould in his Rochdale flat. His father, Faisal Abdullah, had repeatedly pleaded with Rochdale Boroughwide Housing (RBH) for help. “They don’t do anything for you. It’s heart-breaking,” he says.

During the inquest, Coroner Joanne Kearsley posed a stark question: “How, in the UK in 2020, does a two-year-old child die from mould in his home?” She urged the government to take urgent action to prevent more deaths.

Five years have passed since Awaab died. The troubling question now is why, even after such a devastating case, mould continues to plague so many British homes, and whether enough is being done to change that.

Awaab’s law and where it falls short

In July 2023, new legislation was approved to better protect tenants from dangerous housing conditions. The measures, becoming active this month, are collectively referred to as “Awaab’s Law.”

Starting 27 October, social landlords in England must inspect damp and mould complaints within 10 working days and make safe any hazards within five days after inspection. Urgent problems, like gas leaks or severe mould affecting health, must be assessed within 24 hours.

If the landlord cannot meet those deadlines, they must offer tenants alternative accommodation. Persistent failure allows residents to go to court or use the complaints process.

However, these rules currently only cover the social rented sector: council homes and housing associations. They do not yet apply to the 4.6 million households who rent privately. The government has said the law will extend to private tenants but has set no timeline.

Campaigners say the delay limits the law’s impact.

Health toll of cold, damp housing

Hannah, a respiratory nurse in North East England, regularly treats patients whose asthma attacks and infections stem from poor housing.

“In the areas I work, mould-related breathing problems are incredibly common,” she says. “We see the damage every day.”

Living with mould increases the risk of respiratory conditions, allergies and infections. A 2021 BRE report found that the NHS spends roughly £1.4bn each year treating illnesses linked to cold or damp homes.

The issue disproportionately affects lower-income families and older adults. Nearly half of the children living in damp homes have low household incomes. About 324,000 people affected are aged 65 or above.

Awaab’s death stands as a tragic reminder of what neglect can cost.

Years of warning signs ignored

Throughout Awaab’s life, he struggled with cold conditions and breathing difficulties. He died in December 2020 after going into respiratory and cardiac arrest. He was just two.

Barrister Christian Weaver, who represented the family, said the inquest revealed how many times help was requested. “They complained for years. A health visitor contacted RBH. Even someone from the landlord’s team saw the flat. Yet nothing changed.”

The coroner concluded that the home lacked proper ventilation, directly enabling mould growth.

RBH says tenant safety is their top priority and insists they have improved their processes ahead of Awaab’s Law. They encourage residents to report any damp issues quickly and say they are planning for the law’s expanded scope.

A widespread housing issue

Mould thrives in moisture, warmth and poorly ventilated spaces. Tenants can take small steps such as keeping windows open, avoiding drying laundry indoors and not overheating spaces. But many causes are structural: leaks, inadequate ventilation systems or poor insulation.

Housing pathology expert Michael Parrett says damp has become a long-standing nationwide crisis. According to him, moisture problems are often misdiagnosed, leaving root causes unaddressed.

Is current law enough?

Housing Secretary Steve Reed argues the legislation will force landlords to act faster and give renters a stronger voice.

Yet many campaigners say urgency is needed to bring private rentals under the rules.

“The government has been silent on when private renters will get the same protections,” says Tom Darling from the Renters Reform Coalition. “It needs to happen quickly.”

Private renters are statistically most likely to live in properties failing to meet “decent home” standards. In 2023, 3.8 million English homes did not meet that standard. Of these, 21 percent were privately rented.

Shared-ownership tenants also fall outside the new protection.

Even so, some see Awaab’s Law as progress. Housing Ombudsman Richard Blakeway calls it a “crucial step” toward safer housing.

Risk of landlords sinking under pressure

Repairs rules will be phased in and tied to other safety hazards like electrics and structural stability. But critics warn that without better funding for councils and housing providers, the burden could be overwhelming.

“It is going to put landlords under huge strain,” says Parrett. “Some are already stretched thin. It could set them up to fail.”

Budget-strapped local authorities may also struggle to meet requirements. The Local Government Association has urged for more financial support so standards can realistically be met. The National Housing Federation agrees the law’s goals are right, but compliance will be a challenge.

What matters most to affected families is preventing further tragedies. After years of campaigning, they want action to move faster than mould can grow.

“A lot of people shouldn’t have to go through what we did,” says Awaab’s father.

“Deaths like this can be stopped,” says nurse Hannah. “We pride ourselves on progress in public health, but reality is lagging far behind. Too many people have been failed.”

BBC News, October 2025